We gradually dry out and make our way over to the Brazilian side where we are staying at the Hotel Los Cateratas, appropriately named for its stunning panoramic view of the whole set of falls – widely regarded as the widest in the world. Having visited Victoria Falls and Salto Angel in Venezuela (the highest in the world at one mile) this is completing something of a set. The hotel is low slung and colonial in feel, not dissimilar in fact to the Victoria Falls hotel. Weaver birds chatter in and out of their nests and an iguana wanders idly around as we take a beer in the pool area. The plan to watch sunset over the falls, and possibly even moonlight, is scuppered by a massive storm that cuts the power. Instead we sip caipirinhas and marvel at the lighting cracking across the night sky.

It has all blown over in the morning, providing a beautiful opportunity to see early light on the whole scene. Blue jays and toucans squabble over territorial rights, strange large centipedes criss-cross the trail, and an agouti (a large rodent about a metre long) is out scent marking his territory. Swifts nest behind the falls, darting in and out constantly, while herons poke about for fish, and the ubiquitous vultures cruise overhead. There is a rainbow at every turn, and the rising plumes of spray turn rapidly into clouds. Magical.

There is just time to visit the local bird park before leaving. Every imaginable kind of parrot is here; macaws, the huge Harpy Eagle, flamingos, butterflies, hummingbirds, and some very inquisitive toucans. It’s Christmas day, but everything is carrying on as usual. We head to the airport and fly to one of the world’s biggest cities, Sao Paulo. With a claimed population of 29 million, this is truly a megalopolis, and very much the economic powerhouse of the country. The Paulistinos are a busy lot, combining the locals with significant immigrant populations of Japanese, Italians and Germans. Founded in 1554, they are a proud gang and regard those in Rio de Janeiro as fierce rivals. The city is on a plateau in the highlands of South East Brazil, in the middle of what remains of the Atlantic coastal forest. Sadly, only 7% of this now remains.

Sao Paulo provided a staging post en route to the interior. A 2 and a half hour flight to Cuiaba via Campo Grande lands you in the heart of the Mato Grosso. This is gold country, where the Portuguese and Spanish squeezed as much as they could out of the landscape. The Cuiaba River, named after the shiny offers that once frequented it, forms the backbone of the area, which is a basin surrounded by feeding mountains. Huge volumes of water drain into and out of here every year in a regular pattern. These seasonal swamplands are the Pantenal, home to a vast range of wildlife. Heading south the land changes from agriculture to cattle country, much of it underwater. Hawks, parrots, herons and egrets, the massive Jaribou stork with its 3 metre wingspan are all here. The raised road is interspersed with more and more wooden bridges. We stop to let an iguana cross the road, a pair of caracara are harassing smaller birds by the wayside, and capybara and cayman lurk in the shallows.

We arrive at Araras Eco Lodge and walk 1 km into the forest to an observation tower. The heavens open and we receive a fully-clothed shower for 20 minutes. This is en route to the monkey tower, a 60 foot elevated platform above the canopy. We climb it and survey the bleak nothingness as the rain pours down. Then lightning cracks right overhead, rattling the tower and surrounding trees. This is not safe so we beat a hasty retreat, returning the next morning at 6am to watch the sunrise. There isn’t one because it’s too cloudy but there are still monkeys waiting to greet us. The leader of the pack comes and sits down with us for a while, then takes his leave by skiing down a support cable to join the rest of his troupe. One level down, I come face to face with another one curled up and sleeping. A hearty breakfast is followed by a trek through the neighbouring ranch. A pair of caracara staunchly defend their food against a persistent black vulture. Alligators can be spotted imitating logs in still creeks. Blue macaws cackle, an agouti ambles up the track, ibis and herons adjust their positions at the waterside, and a variety of hawks – savannah, roadside, collared and more – survey the landscape disguised as branches. If it weren’t for the mosquitoes this would be perfect.

In the afternoon it is time for a bigger adventure – an aquatic one. We clamber into an open backed truck and take a one-hour drive on the main road. There’s no tarmac and our teeth rattle in our heads as we rumble over potholes and water-filled gulleys. Bursts of mosquitoes harass us and we stop every now and then to observe the animals. Off the main drag now and it’s a mud track, fording rivers and aquaplaning through the low fields. At the height of the wet season this is all under a metre of water, with access by boat only. We arrive at the banks of the Rio Claro, and head up river. Alligators brood menacingly on the banks; hawks and herons survey the water; kingfishers dart in and out.

As we approach an alligator in mid-stream, the boatman whips out a fishing rod, attaches a fish and dangles over the edge. The caiman smells it and homes in. We get to observe first hand how they grab their prey. A leap from the water, a twist and roll. “Don’t try this yourself”, he smiles, holding up the stump of an index finger from a previous encounter. Two storks came cruising down the river, white wingspans of 3 metres apiece, coming in to land. We pull up and throw them a fish as a vulture looks on, hissing periodically and waiting for leftovers. Another local trick next, involving a collared hawk, a large russet brown fish-eating bird of prey. Spotting one idly perching in a tree, the boatman whistles, waves a fish and hurls it into the river. Down he comes, wings splayed, brakes on, yellow talons out, and he’s off, with a screech of ‘thank you’ to the boatman. It’s all over in a flash and that’s too quick for the camera – further evidence of the fine art of the wildlife photographer.

On the way back it’s time for a spot of piranha fishing. This is something I have done before in Venezuela on the Orinoco. A simple bamboo rod and line, a single hook with a bit of chicken as bait, and you’re in business. They’re nibbling straight away and five minutes later I have my first fish. It’s a decent size, maybe six inches long, a yellow-bellied variety. We perform the post-catch ritual of exposing its razor sharp teeth for the camera, and it goes into the pot. As they keep biting, we end up with thirty or more, which the boatman will turn into a decent dinner. We rattle back to the pousada in the truck. It’s been a good day but I’m getting hungry and the various bird species we encounter on the way home look more and more appetising as the minutes tick by.

The next day it’s time to leave the Pantanal – this fantastic alluvial plain teeming with life. We take the 3 hour drive north to Cuiaba, past the ethanol factory and the football stadium where they will host games in the 2014 cup, and to the airport for our flight to Alta Floresta. This is due north, still part of Mato Grosso but deep into the Amazon, at the northern edge of Amazonia state. The twin-prop takes us via a stop at the strangely names Sinop, which turns out to be an acronym for Sociedade Imobilaria Noroeste do Parana. The Amazon was named by the Portuguese after the mythological Greek race of female warriors – not that anyone ever saw such people. They just liked the idea of finding them. Sinop is essentially a hangar in the middle of a vast plain full of fields turned over to agriculture. The scale here is massive: the whole of Europe would fit into the Amazon with room to spare. Hundreds of miles of rain forest have been chopped down and the land reorganised for crop production. The lungs of the world are being reduced by the day.

Alta Floresta is on the southern fringes of the Amazon rain forest. We are met by Renato, who runs the local ecological foundation, and Vitoria, who set up the Cristalino Jungle Lodge. Renato shows us around his offices and explains their purpose – to protect the forest from further deforestation and work with local communities to educate them. There is a liaison with the botanical experts at Kew Gardens, an arrangement with DEFRA, and a jaguar conservation project with Oxford University’s WildCRU. We had hoped to stroll into the forest to visit the nesting site of the Harpy eagle, the biggest of them all, but sadly she had moved on two months before so there was nothing to see. A hint of the wildlife to come was provided by a specimen cabinet in the hotel reception containing the obligatory tarantulas and some moths and bugs as big as your head. Dinner was uneventful apart from an armadillo running past our table.

In the morning we set off with Vitoria for Cristalino. After ten minutes the jeep sprang a leak and we had to call for a replacement. Then on into the forest for just under an hour before arriving at the banks of the Teles Pires river, where we take a 20 minute boat ride up one of its tributaries, the Cristalino. This will be our home for the next three nights, and an unusual chance to become thoroughly informed about the local flora and fauna, and efforts to conserve them. There are more bird species here than anywhere else in the world (around 600) so many of their visitors are compulsive birdwatchers. A short hike before lunch reveals plant leaves with anaesthetic qualities that numb the tongue, arsenic, intense poison ivy, bamboo-like vines with drinkable water inside hollow sections, trees whose roots move depending on sunlight, strangler figs up to 300 years old, bizarre fungi, and much more. A pair of curussow wander past, a diurnal owl swoops past, a woodpecker hammers at a nearby tree, and we come across a dead tarantula suspended from a leaf, killed by eating the poisonous plant from which it is still suspended.

There are certainly some very strange things in the jungle. The medicinal properties of the plants are extraordinary, capable of curing kidney stones, alleviating dental pain and much more. Liquid sap that tastes like milk and can sustain you for days. A brazil nut tree estimated to be between 600 and 800 years old. Its seedpod reaches around six inches in diameter and has two solid layers. Only the determined agouti can get into it, and that takes two days of gnawing. We hacked it open to guess the number of nuts inside – 24. White whiskered spider monkeys hurled abuse from high up in the canopy, banging branches in aggressive postures. A large burrow under a tree suggests an armadillo burrowing for ants. It is also a perfect home for a tarantula, and there she is, revealed by torchlight, the size of a hand with yellow tipped feet. Countless species of bird come and go. Our guide Alfredo can imitate most of them – call and answer between man and animal. The musical wren sings a waltz theme – Alfredo answers.

Returning home, Sarah finds a spider in her shoe, about an inch across, and at this stage well protected by thick socks from doing any damage. She whacks it and it disintegrates, but half of the body is embedded in the sock and a huge curved stinger springs out. With the legs still twitching I carefully unhook the dangerous looking parts form the material and wash it down the sink. You never know.

The following morning we are joking about the two most difficult things to see round here – the Harpy Eagle and the jaguar. Ten minutes up the river and there it is: a young Harpy high up on a tree. This is the biggest eagle in the world, feeding regularly on monkeys. Jubilant, we climb a rocky trail to a 250-foot high vantage point and say hello to a pair of vultures, some dangerous looking spiders, and leaping monkeys who apparently have no fear of heights. Some mysteries are revealed, others not. The tantalizing scratch marks of a jaguar on a tree; tapir footprints at a saltlick; armadillo and anteater burrowings, but the animals long gone; birdsong revealing the presence of the owner but not the sighting. Others do: a spider that builds its own trap door; a cicada that builds a six-inch protective tower – strange indeed.

In the afternoon we motor up river, cut the engine and drift all the way home, listening to the ‘silence’ of the jungle and watching the sunset on the way. A refreshing swim in the brown, tannin-filled water caps off the day. At dawn we ascend an enormous tower that reaches high above the canopy, nearly 200 feet. The mist is still rising off the jungle as we spy a range of waking animals: monkeys, parrots, toucans, and the bright turquoise plum throated cotinga (with a plum coloured throat of course) and a pompadour cotinga (burgundy with white wings). We ford some small streams and lurk in a tree house enjoying the forest sounds.

It is New Years Eve, and the festivities include as many musicians as possible, including me, playing whatever instrument they can to provide the entertainment. Most remarkable of all is a girl who uses only her body as a percussion instrument. Apparently she is in a band of this type that has fourteen people in it. Dinner is briefly interrupted as an eight-inch tarantula turns up underneath the table, and the survivors end up on the pontoon deck on the Cristalino river drinking champagne. We leave the Amazon the next day and fly via Alta Floresta, Cuiaba, and Brasilia to Rio de Janerio, erroneously named because the guy who discovered it thought it was a river when in fact it is a bay. It’s a lively city surrounded by the famous sugar loaf mountains. The Indians called the main one pau-nh-acuqua meaning ‘high peak’ which the Portuguese thought sounded like pao de acucar, a loaf made of refined sugar cane. There’s a cable car on top of it but not much else, so we decide to go up one with Christ the Redeemer on it. After pointless stops at a stairway made of tiles and an arts and crafts shop in Santa Teresa, the so-called bohemian quarter, we are rewarded with high views of the city. The 14 km bridge across the bay is unsightly, and the northern view is mainly a mess. A favela, or drug-ridden slum area, creeps ominously up the mountain.

Queues of yellow taxis snake up to the summit, clogging the tiny roads. Thousands of baying tourists pour out of the nearby station and stampede to the top, hurling Coca Cola bottles behind them and contorting themselves to take strange-angled photos of the 30 metre high statue. Everybody is pushing and shouting. There is no humility or respect for this significant religious icon, recently voted one of the seven wonders of the world. The whole unseemly scrum reminds me of the dismay I felt when visiting the Taj Mahal: no restriction on numbers, even though it is in a National Park; no code of conduct; no dignity. As the helicopters buzzed overhead, the best one could draw from the experience was the spectacular views of Ipanema and Copacabana. We returned to our hotel in the heart of Ipanema’s gay sector, the Crystal Palace, to drink caipirihnas and watch the homosexuals strutting past in their skimpy luminous trunks. As we ate dinner, we watched men stop the traffic and show their skill at Capoeira, an athletic type of combat dance based on martial arts.

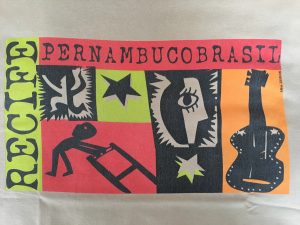

Then we are off again – to some little known islands off the north east coast called Fernando de Noronha. It’s 1200 miles to Recife, the African slave influenced city on the shoulder of Brazil. From here it is a short flight to the ancient volcanic islands: a national park that is spider free but full of turtles, dolphins and frigate birds. After being fought over by the Dutch and Spanish, the islands were given to a Portuguese guy called Fernando de Noronha, who never actually bothered to visit them. Since then they have been used as a technical centre for Air France, a refuelling airbase, and to house US guided missiles. But nowadays activities are less intrepid: surfing and snorkelling. The Pousada Miravilha turns out to be one of the best hotels in the world, and I’ve seen a few. An idyllic view over the Sueste Bay, filled with turtles and very little else. A maximum of 500 people allowed in on any given day. One main road with only dune buggies allowed. The whole place is a national park. Frigate birds cruise the shores in squadrons. Cattle egrets sip from the swimming pool. 3-foot lizards scuttle into the undergrowth as you approach, along with moco, small chipmunk-like rodents that arrived in 1967.

We have a dune buggy to explore the island: a couple of rusting old canons on the northern tip; a tiny main strip with various tracks heading down to the shoreline. Huge pointed volcanic rocks provide easy landmarks for orientation. The occasional ruined Portuguese fort is interspersed with probably the most unspoilt beaches in the world. On the northwest coast, huge waves and endless sand create a Mecca for surfers at Praia do Americano and do Bode. The Baia dos Golfinhos provides a 50 metre high vantage point for spotting frolicking spinner dolphins, and vast areas of woodland are cordoned off to help regeneration. On the southern tip, Praia do Leao (Lion Beach) feels like the best in the world: perfect sand, crashing turquoise waves, dramatic black volcanic shelves off to one side, huge pointed pitons providing an imposing backdrop and, crucially, just a handful of people. To cap it all, the Mirante das Caracas provides one of the most stunning ‘end of the world’ vistas one could ever wish for. On a southwestern point, the Atlantic winds whip in with a 3000 mile run up, colliding on huge black volcanic shelves with a counterblast swirling round from mainland Brazil. A quick calculation suggests that heading directly south from here would give you a clear run to the South Pole, some 5,000 miles later. No wonder the waves are wild.

Praia do Leao is a different proposition in the morning when the tide is well out, revealing an extra 50 feet of golden sand, and the black volcanic shelf that surrounds much of the island. This is snorkelling weather, and we head out to the rocks, under the shadows of the huge morro which resembles a Sea Lion and so gives the beach its name. Large blue neon parrot fish peck away at the rocks and small pilot fish form flotillas to follow you along. Near the shoreline the ubiquitous frigate birds dive bomb the shallows and oyster catchers sweep up what the waves bring in. Small fish dart around the volcanic rock pools as crabs scuttle into crevices. In the afternoon we transfer operations to Sueste beach, with a specific purpose: we are in search of the turtles that nest here. The national park protects them, planting warning sticks on the beach were nests have been laid. Eggs tucked 70cm below the surface will hatch 40 days later and after hatchlings have struggled into the sea, they will return to the same beach 20 years later to lay themselves. We snorkel out to the prime area. It’s a bit crowded for a designated national park, partly because we have sheepishly all come at the suggested high tide moment. Our efforts are rewarded though, with half a dozen of these 4-foot monsters. As they wave languidly along, one wonders how they hold their breath for so long. Our guide says their lungs are huge, and they have been observed sleeping underwater. There’s additional fun to be had when they do eventually surface for air: holding one’s mask half out of the water provides a charming moment when their faces break the waterline and reveal their true colours. A large spotted stingray, its tail at least three times the length of its 2-foot body, completed the show on our way back.

Reflecting on Fernando de Noronha on the final evening in front of a classic crimson sunset, one had to conclude that this is one of the most perfect spots on earth. The climate is divine: warm, not humid, and with a constant refreshing onshore breeze. The landscape is stunning: volcanic spikes punctuating a dramatic seascape. The wildlife is nicely balanced: no spiders or mosquitoes but plenty of birds and marine life to keep you amused. The beaches are probably the best in the world (one here was recently voted best beach in Brazil). The transport is fun: dune buggies up dusty tracks as though you have a bit part in Banana Splits. The hotel is superb: great food and charming service. Frankly, there is absolutely nothing to dislike. If you want to, you can even get sky TV, internet and full mobile reception, none of which are really the point.

Leaving the islands was a little more complicated than arriving. Most flights are heavily oversold – a very poor aviation practice – and despite confirming our tickets we were informed that we would not be on the flight. After protesting that we had reconfirmed and pointing to our flight connection in Recife, we made it onboard and bid the islands farewell. The connection worked even though we had to reclaim our bags and check in again, with a quick plea to First Class check in to help us along. A short flight straight down the coast brought us to Salvador, the original capital of Brazil, with a 3 million population (90% African origin) and the second largest bay in the world, behind Hudson Bay in Canada. It’s a chunky place, with significant trade in oil, sugar and gems taking place. We drove to the Pelourinho area, the cobbled old town where you are advised only to go out in a taxi, which we did, to an excellent French restaurant.

The next day we were bound for the interior – 300 miles west, via Feira de Santana, through the Reconcavo agricultural belt full of banana and sugar cane plantations. Gradually this gives way to cattle ranches covering the vast expanses one comes to expect in Brazil. The occasional herder and horse; cattle lolling around waterholes dug by their owners; buzzards and vultures a constant presence overhead; carefully overtaking the slower lorries with their ingenious wheel pipes that top up their tyre air on the move. Soon foothills appear, and the odd morro, of mojotes in Cuba – freestanding rock outcrops betraying a former rocky plateau. And then there we are: Lencois in the middle of the Chapada Diamantina. This is a boom and bust town in diamond country. When the French prospectors originally congregated here, their tents looked like laundry in the valley, hence the French Lencois. We scale the slope to our hotel and nestle into a well-earned beer after out 5-hour drive.

A range of activities is on offer the following day. First we drive to the caves at Lapa Doce. This is a wonderfully large underground river, long since dried up. Descending 70 metres past a range of wildlife, including another of our old friends the trapdoor spider, we walk for a kilometre along the old riverbed. The chamber feels about 100 feet wide and 50 feet high, with soft sand underfoot and a range of bizarre shapes on show. As we pad quietly along our guide uses an old lamp to illuminate some superb features: stalactites and stalagmites, growing one centimetre every 33 years; some are complete pillars now; great fans of white crystal; red, iron-stained bulges; water pools; bats; shapes that look like people, angel wings and a range of animals. By putting yourself in the right position and then waving the lamp, you can make your shadow appear to ride lions, turtles and more. There’s even a Mexican who seems to have been eaten by an alligator. We return to ground level and drive on, this time up to the Pai Ignacio plateau where we climb to the top for brilliant views of the whole area. You can see for miles, the landscape feeling rather like a well vegetated Grand Canyon. Then on to the Mucugezinho river which runs lazily in the valley. A short stroll to the Poco de Diablo waterfall, the third time on this trip we have been exposed to a part to this devil’s anatomy.

It seems every feature of the country has a story behind it. This is the devil’s mouth because slaves who misbehaved were supposedly thrown off the top. Pai Ignacio was named after a priest who was caught having an affair with the top man’s wife. After being chased up the hill he jumped off, opened his umbrella (always available in Brazil), and parachuted down to a hidden ledge, surviving his pursuers. This is clearly utter rubbish, and the locals eventually admit it. We dive into the highly refreshing tannin-stained pool and take a power shower under the waterfall. A robust barbeque lunch winds up the afternoon before returning to the hotel and drinking some extremely dangerous cachaca called Pirassununga. If you ever come across it I advise that you stay well clear unless you have run out of fuel for a piece of heavy machinery.

The next day was billed as more strenuous and so it proved to be. We were to hike to the Sossego waterfall, a round trip of 10 miles over some tricky terrain. Two and a half hours was the average time to reach the falls and we set off at 9.30am, initially through forest and then emerging onto a rocky plateau. These were conglomerate rocks, a mix of volcanic, quartzite and sandstones, all thrown together in a stew and dumped in cracked slabs along the valley. Less cover now with the sun rising higher as we hugged the river up to its source, sometimes climbing over crags, other times crawling under them. We arrived at midday. Sossego means relax and that’s precisely what we did, diving into the perfect plunge pool, about 100 feet in diameter, to swim to the fall on the other side for a vigorous and slightly stinging power shower. The water is so pure that you can drink it, which is how we refilled our water bottles along the way, just as we drank from the glacier in Argentina.

We had the pool to ourselves for about fifteen minutes, by which time about thirty other people turned up and the place became a circus. Young men showing off in improbably tight trunks jumping from the highest ledge they could find whilst the women looked on, bored. We cherished the peace we had experienced moments before and decided to move on. Back down the valley we travelled further down river to Ribeirao de Meio, another refreshing pool with an intriguing natural water slide. A huge 100-foot square slate tilted at a gentle 45 degree angle, eroded smooth by the river and naturally lubricated by the water. By climbing the dry side and getting one’s position right, a decent toboggan run could be achieved sitting upright – a good 70 foot run with a superb plunge into the pool at the end of it. Your arse takes a bit of a pummelling but it was worth it. Exhausted after our 5-hour endeavour, we returned to the hotel to drink ice cold beer in the swimming pool as we massaged our muscles – but not before we watched a troupe of tiny macaque monkeys eating mango and springing around in the trees.

Time to move on again. Up at 4.30 to drive from Lencois to Salvador airport. Then fly to Rio, back to Ipanema, home of the strutting homosexuals in nothing but luminous green pairs of pants, and the occasional ornamental poodle. On the previous visit, I was having a drink in a bar with my arm resting on an adjacent chair when one of these characters squeezed past, effectively impaling his butt cheeks on my elbow. I suppose at least the trunks served as a form of prophylactic. Moving now to the very final phase of the trip: a beach-based finale in the highly hip area of Buzios, a three hour drive north of Rio on a small peninsula. We cross town on a busy Saturday and straddle the 12km Niteroi bridge which spans the Guanabara Bay. Ugly from the heights of Santa Teresa, it nevertheless links the city effectively with the northeastern side. We arrive in Armacao de Buzios around 5pm and are checked into the chic Casas Brancas hotel. This is a beautiful bay where the boats come and go – an Atlantic St.Tropez. Much is made of the fact that Bridgette Bardot once visited in 1964. Given that is over forty years ago you would have thought they should get over it and offer up somebody more contemporary. Passengers queue on the quay to be ferried to the huge cruise liners moored off shore. Couples promenade along the seafront, being splashed by the occasional unexpected breaker as the tide comes in. The sun sets in front of our balcony as a perfect crescent moon rises. Dinner overlooking the bay is a pleasure.

And so to final thoughts and reflections on this extraordinary trip. Many would say a trip of a lifetime but once again the proof is there that there are many such trips waiting to happen, so long as the desire, time and resources are there. After the delights of Chile, Bolivia and Venezuela, this is further confirmation of the lure of South America. Big cities can be lack lustre the world over, and Buenos Ares was no exception. We’ll take it as read that the place is based to a large extent on character, because there is little to recommend it on the basis of environment, architecture or culture. Sao Paulo looked huge and amorphous, although we didn’t have time to explore it, but Rio was a success overall. An extraordinary backdrop of mountains and sugar loaves, a relaxed attitude, miles and miles of beach. The Guanabara Bay is so vast that one almost forgives the Niteroi bridge and the heavy industry. The commercialism and lack of respect at the scene of Christ the Redeemer, however, remains a black spot.

Natural phenomena come in waves. The Perito Moreno glacier in Argentina; the view alone; the milky lakes; walking across it and drinking the glacial water; watching the ice calve off the end with a boom; sailing alongside icebergs the size of shopping centres; and observing the seemingly endless Andes from 30,000 feet. Iguazu Falls, charming from both the Argentinian and Brazilian sides. “What time is it?” I asked our Brazilian guide as we crossed the border. “One hour ahead,” he replied, “Brazilians always ahead of Argentinians.” Up close and personal in Argentina, including the thrill of going under the falls in a boat. Broad and panoramic in Brazil, observed at night in a dramatic thunderstorm, and then without a soul around on Christmas Day morning.

Wildlife galore. The Pantenal with its abundant hawks and herons; feeding an alligator from a boat; consorting with storks and capybara; feeding collared hawks and caracara; fishing for piranha. And then onto the Amazon: scarlet macaws; the harpy eagle, a variety of tarantulas, and an unforgettable new year celebration in the jungle. But there was more. The rugged beauty of Fernando de Noronha, probably the best island in the world; swimming with turtles and rays; the African influence in Recife and Salvador; fantastically rewarding trekking in the little-known diamond country of Lencois; the views from the top of mountains, inside caves and under waterfalls. All capped off by an idyllic final stay in the bijou town of Buzios; with its Mediterranean ambience and Brigitte Bardot statue sitting coyly on a promenade bench. The fact that the whole of Europe fits comfortably inside the Amazon basin alone provides an indication of the sheer scale of Brazil. There is so much to investigate that the job could never really be described as finished. Quite so.

As a footnote, on returning to the real world after one month and 25,000 miles, I found I had received over 3600 spam emails, an average of more than 100 a day. That’s modern life for you.

Leave A Comment